Repair work can rewarding and a nice change from building furniture. The following is how I repaired a client’s chair that had been broken during a move.

Some of the damage to the chair is apparent from the picture below.

The first step is to test all the joints and find out which ones are loose. I marked the loose joints with blue painters tape.

Loose rungs are best fixed by removing the entire rung. This allows you to scrape the old glue off . If you are lucky the old glue is hide glue. If the chair is old and remnants of the glue dissolve with water, chance are you dealing with hide glue. This chair was not built with hide glue, which means new glue will not stick to the old dried glue. The old dried glue must be scraped off of the tenon to expose fresh wood so the new glue has something to adhere to. Of course, this scraping process removes some material so it loosens the joint. In my case most of the joints in the leg stretchers were loose enough that a blind wedge was required to fill the gaps.

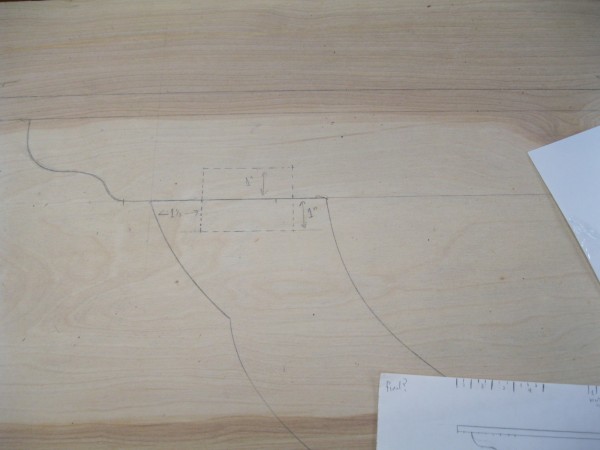

To make a blind wedge cut a kerf in the end of the tenon . . .

and insert a wedge. The depth of the tenon’s mortise must be considered when making the wedge. The wedge must be long enough and angled enough to spread the tenon into the mortise, but not so long that the tenon spreads too much (or the wedge bottoms out in the kerf before it fully seats).

Although you can’t see them (hence the name “blind wedges”), there are wedges in both ends of the rung between the clamps. Clamp pressure forces the wedges into the kerf. The clamp on the top of the leg is holding the leg for alignment purposes only.

The top of the leg is glued and doweled in place. I don’t trust glue alone so a Miller dowel was inserted (the end of the dowel was trimmed after I took the picture below).

A chunk off the end of the broken arm rail was barely hanging on, I completely removed the chunk with hand pressure.

I glued the chunk back in place and pinned it with dowels for reinforcement (I forgot take pictures when drilled and inserted the dowels). I like to make my own dowels using a Lie-Nielsen dowel plate.

After the chunk was glued back in place a inlay strip was needed to fill the gap left by some missing splinters. The inlay strip will also help hold the chunk in place. I placed a strip of cherry over the gap and traced it with a knife.

I evacuated material inside my knife lines using a chisel to create a square recess for the inlay strip.

Here is the strip after it was glued in place.

I trimmed the excess with a chisel.